The building of railroads was big business in the 19th century. It changed the face of America and of Greenwich. Of four railroads that were planned through Greenwich, only one, the New York New Haven and Hartford, was actually built. After it opened in 1848, New Yorkers came to live here, and people commuted to work in the city. As food could be shipped quickly by rail, consumers depended less on locally grown produce. Farmers were able to sell their land profitably to New Yorkers who liked country living.

One railroad, the New York Housatonic and Northern, was planned in north Greenwich. Even though it was never built, this line also changed our town, but in different ways.

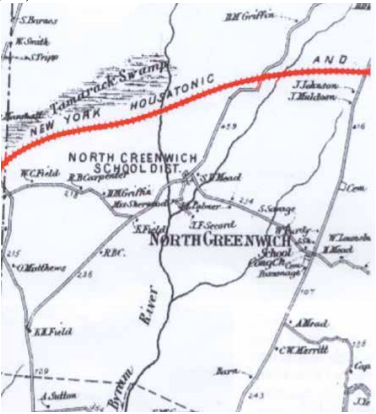

The New York Housatonic and Northern was planned to go from Port Chester to Danbury and north. The 1867 Beers Atlas shows this railroad as existing, but the railroad was never actually completed. Construction of this railroad began before the Civil War. As there were no gasoline engines then, rock was drilled by steam power, and grading was done by horse and hand scoops. Most of the roadbed was leveled and rails were brought in, but no track was ever laid. The New York, Housatonic & Northern railroad went bankrupt and did not renew its charter.

In 1912-1914, another company, The Millbrook Company, planned to finish the work on the New York, Housatonic & Northern line as the New York, Westchester, & Boston Railroad. A wealthy New York lawyer, John Sterling, bought up 1400 acres of farmland in north Greenwich and North Castle, speculating that the railroad might bring development and make the land more valuable. After the war, automobiles became the preferred means of travel, railroads declined, and building stopped. Sterling died in 1918 and left his farmland to Yale University, its largest bequest to date.

Yale called the land Yale Farms, named the roads after Yale presidents, rectors, and Sterling himself, and began selling. Yale sold some lots before World War II, but many were still unsold. After the war, the United Nations formed a committee to find a permanent site for its head-quarters. The committee wanted an area of 42 square miles that could be expanded to 172 square miles. It considered areas within Greenwich, Stamford, and North Castle, New York, where it found the 1400-acre Yale Farms and 1500-acre Lewis Rosenstiel land (now Conyers Farm).

When this news came to Greenwich in late January, 1946, it galvanized local leaders. The advocates believed that the U.N. would be good for Greenwich as well as for the world and that only a few families would be displaced. The opponents were careful to state that they were not opposed to the United Nations or world peace, but that a new home for the U.N. should not take over existing homes and that the proposal would overtax the town’s water supply, sewage capacity, and traffic system.

In three days the opponents formed the People’s Committee to oppose the U.N. in Greenwich and collected 930 signatures and $29,000. When they heard that a representative of Yale had offered Yale Farms to the U.N. site committee, the university denied having made such an offer.

An overflow crowd of more than 1,000 attended the February meeting of the Representative Town Meeting in the Greenwich High School Auditorium, and the RTM voted to hold a referendum on March 2, 1946. The referendum showed 5,505 opposed and 2,019 favoring U.N. headquarters in Greenwich. When the U.N. search committee learned of this opposition, it abandoned its plans to move to Greenwich. In December, 1946, the U.N. assembly voted to build on the East River in Manhattan on a site offered by the Rockefeller family. The Greenwich People’s Committee refunded 30% of all donations on Christmas Eve, 1946.

And so, thanks to the railroad that never was, Yale got its Sterling Memorial Library, Sterling Chemistry Laboratory, Sterling Divinity Quadrangle, Sterling Hall of Medicine, Sterling Law Buildings, Sterling Power Plant, Sterling Quadrangle, Sterling Tower, and 28 professorships with his name on them. Some traces of the old railroad bed can be seen between Bedford and Round Hill Roads and the area is now home, not to farmers or the United Nations, but to residents who may enjoy knowing how this place came to be.name on them. Some traces of the old railroad bed can be seen between Bedford and Round Hill Roads and the area is now home, not to farmers or the United Nations, but to residents who may enjoy knowing how this place came to be.